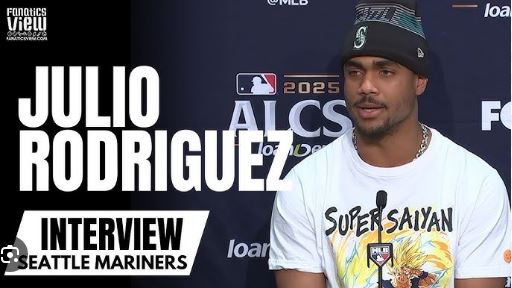

LATEST UPDATES: GROUND BREAKING NEWS REGARDING Julio Rodriguez RETURN

That’s the fast version of the Julio Rodríguez story. It is apropos to the Mariners’ center fielder and the way baseball will be played this year. Julio is fast. Fast runner. Fast talker. Fast learner. Fast tracked.

Fast like baseball in 2023. In the time it took you to read the fast version of Rodríguez’s story, two pitches could be thrown in a major league game—not one, the way it was for years.

Sacrilege became necessity. Major league baseball for the first time will be played with a clock: 15 seconds to deliver a pitch with the bases empty and 20 seconds with runners on. Other new rules include a ban on defensive shifts, a ban on positioning infielders on the outfield grass, bigger bases and a limit of two unsuccessful pickoff throws during a plate appearance. It is the most seismic one-year suite of changes ever made to how baseball is played.

The goal of the rule changes is not just to increase the pace of action, but also to return the game to the players after years in which playing style was dictated by front offices following analytics as their North Star. The result of data-driven baseball was an aesthetic disaster and a commercial flop.

Nobody better represents the ideal version of this new era of baseball than the J-Rod Show. Faster. More athletic. More daring. More unencumbered. More fun.

His perpetual smile is a happy contagion. His joy is a burst of neon light. More than sprint speed or exit velocity, the gift of this 22-year-old is a je ne sais quoi that makes him simultaneously swaggy and endearing.

“If you don’t know the kid and you see the necklace, the J-Rod Show and the YouTubes, it wouldn’t be convincing how genuine he is,” says Mariners assistant general manager Andy McKay, who has known Rodríguez since he signed at 16. “If you are around J-Rod you see it and you believe it.”

“I’m just a guy who came from Loma de Cabrera, a town in the Dominican Republic with 20,000 people, and one day I can be hitting in front of 50,000 people in Dodger Stadium with the whole United States watching it,” Rodríguez says. “I want to inspire those after me. You can get there if you work hard. If you dedicate yourself, you are able to live out your dreams.

“This is a beautiful game when you play it the right way. I feel like there are a lot of people that, um, how do you say it? They take the game too serious. And I feel like they forget about the joy of this.”

In March 2020, Rodríguez, then 19 and a nonroster invitee, walked past the spring training office of Mariners manager Scott Servais. “Hey, Julio. Come on in here,” Servais called out. It was their first meeting. “I was blown away,” says the manager.

How so?

“His grasp of the English language. His confidence. His personality. How sharp he was. Right away I go, This dude is different.”

By midway through last season, just a rookie, Rodríguez had become the Mariners’ best player and one of their leaders. “His personality is like a magnet,” Servais says. “Listen, you can’t bulls— players. When you’re around somebody who acts one way and then when the camera is off acts another, that wears off fast. But this is just how he is. He truly loves baseball.”

He is the right player at the right time.

Since 2007, the game’s attendance apex, to last season, baseball has lost 14.9 million ticket buyers in the regular season and 5.3 million World Series viewers. A changing broadcast and entertainment marketplace contributed to the erosion. But so did a brutally efficient but dreadfully slow, risk-averse style of percentage-driven baseball.

From 2007 to ’22, the average game grew 12 minutes longer with 5.5 fewer balls put into play. As technology gave people more options at their fingertips, baseball operated under a backward business strategy: It kept giving people less action over more time.

Nobody set out to produce a duller game. It was the byproduct of front offices swelling with whip-smart analysts who dived deeper into the game’s rich statistical lithosphere and emerging informational technologies to hack the probabilities. The byproduct of their work almost always squelched action.

Pitching staffs spun the ball more because average spin is harder to hit than extreme velocity. Hitters took full-tilt swings because the occasional home run, even at the cost of more strikeouts, carried a better risk-reward ratio than playing for a rally. Highly advanced defensive positioning encouraged this boom-or-bust hitting approach. Shifts worked so well at sucking hits out of the game that their use nearly tripled in just three years, from 12% in 2017 to 35% in ’20, including more than half the time against a left-handed batter. Runners were discouraged from attempting to steal bases because the risk wasn’t worth it when you are waiting for home runs.

Action and fan interest eroded in lockstep. From 2007 to last season, the information-based style removed 5,302 hits, 623 stolen base attempts and 25 batting average points from the game. Strikeouts went up by 8,623. The ’18 season marked the first time in baseball history strikeouts outnumbered hits. It has remained that way ever since.

As a speedy right-handed hitter, Rodríguez did not suffer greatly from shifts. (He saw them 8% of the time.) But with pitchers now required to work faster (less recovery time between intense effort), more balls expected in play and an expected higher success rate of stealing bases, his hitting and running skills are exactly what baseball wants to highlight to pull the game out of this 15-year aesthetic decline.

Says Rodríguez, “I like it because I feel it is just being able to put on display everything you can do to help a team win. I feel like you push people even more to be complete players.

“I know a lot of people said, ‘Oh, don’t steal bases because it doesn’t really impact the game. It’s not good.’ But 90 feet will always impact the game in a better way. Ninety feet can be the difference between a guy hitting with no outs and a man on first with a chance to hit into a double play and hitting with a guy in scoring position. That can be the deciding run in a game.”

Rodríguez stole 25 bases last season. After a slow start, he also hit 27 homers in his final 99 games, a pace that puts 40 homers within his reach. Only four players have achieved a 40–40 season—none of them everyday center fielders—and all of them did so between 1988 and 2006: Jose Canseco (1988), Barry Bonds (’96), Alex Rodriguez (’98) and Alfonso Soriano (2006).

That Julio Rodríguez deserves mention in such company is another fast story. Not even the Mariners expected him to be this kind of player.

The date was March 13, 2022. After a three-month lockout in which clubs had no contact with their players, the Mariners were back on the field for a workout in Peoria, Ariz. They were running the bases during a routine drill when Servais turned to one of his coaches, Manny Acta, and said, “Omigosh! Manny, did you see that?”

“Hell yeah, dude,” Acta said.

Watching Rodríguez run left them slack-jawed. Until then, the Mariners thought of Rodríguez only as a corner outfielder because of his thick body. He is 6′ 3″ and 228 pounds. It was one reason why Rodríguez signed in 2017 for a $1.75 million bonus, a nice sum but less than eight other international free agents. Corner players are valued less than those who play in the middle of the field. It also partly explains why, as recently as ’20, Rodríguez was ranked below Cristian Pache, Joey Bart and Dylan Carlson on prospect lists.

What the Mariners couldn’t know during the lockout was that Rodríguez had been working in Tampa with a speed coach, Yo Murphy, a former NFL wide receiver. They worked on more efficient form, including a longer stride. When the lockout ended, Rodríguez told team officials he planned to earn the center field job.

“Whenever I would bring it up to them they would go, ‘Ah, nah. We’re going to try to save your bat and put you in the corner,’ ” Rodríguez says. “I felt … not mad, but I was like, ‘Man, you’re not seeing the whole picture.’ Because I feel like I’m restricting myself into the corner when I can play in the middle. Now people are realizing, We were actually wrong about this guy.”

Leave a Reply